This decade started off with a huge triumph for women in space. Astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir made history by completing the second all-woman spacewalk in January 2020, just a few months after having completed the first spacewalk in October. The spacewalk is symbolic of the progress the space industry has made in including women — but it also marked a giant leap forward for womankind in spaceflight.

Over the past few years, there’s been a drive to get more women involved in the science, engineering, and space sectors. Women have been employed in the industry for decades; Katherine Johnson, for instance, was a female mathematician employed by NASA whose calculations of orbital mechanics led to success on U.S. spaceflights. However, it wasn’t until half a century later that her contributions and that of other female NASA employees were finally recognized.

If popular culture is any indication, women are becoming more visible in the industry. Hollywood films in the 2010s like Gravity, Interstellar, and Arrival featured women playing astronauts and scientists. A new book series called Lady Astronauts envisioned what a timeline of women astronauts in space would have looked like and Amy Shira Teitel’s book, Fighting for Space: Two Pilots and Their Historic Battle for Female Spaceflight , tells a compelling story of the early struggles for women entering the space industry.

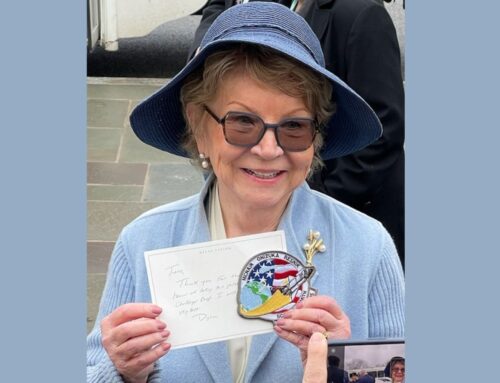

It seems this visibility and inclusion of women in spaceflight is leading to greater equality. Today, the percentage of women amongst new astronaut trainees doubled from 20 percent in the 2000s to 47 percent in the 2010s. However, firsts for women in the industry are still occurring. Beth Moses, a commercial astronaut instructor, became the first woman on a commercial spaceflight aboard Virgin Galactic’s spaceship in February.

Gender Equality in the Space Sector

The progress NASA has made during the last decade has not been without its shortcomings. The first all-women spacewalk was originally slated for March 2019 but was cancelled due to a shortage of spacewalk uniforms in the necessary, typically smaller sizes for women on the International Space Station.

Still, women are hugely underrepresented in space. The ratio of women on the International Space Station has not changed in the 20 years of constant occupation. Women have only compromised 12 percent of the ISS’s population in the 2000s and 11 percent in the 2010s, still remaining a minority on Earth and space.

Fortunately, NASA is continuing to improve diversity work behind the scenes by including guidelines to accommodate employees undergoing gender transition and in 2016, LGBTQ individuals have been included in their nondiscrimination policy. NASA has been voted as one of the best places to work eight years in a row, but its workplace is still relatively homogeneous; 66 percent majority of workers are male, while women and ethnic and most racial minorities are largely underrepresented in comparison to the general population. At the top, 86 percent of senior employees are men. A lack of diversity among leadership, unfortunately, doesn’t properly reflect the experiences and perspectives of underrepresented populations, and the spacesuit incident which delayed the first all-woman spacewalk is just one instance of unintentional bias and of how women are overlooked. NASA has learned its lesson and the newest designs of spacesuits are highly customizable and capable of accommodating anyone in “the first percentile female to the 99th percentile male”. In other ways, space environments are also designed poorly and can overlook women. This waste disposal system aboard the ISS, in particular, is poorly suited to handle the waste of feminine hygiene products. However, the number of female astronauts is too small to assign a detailed clinical trial on how certain hormonal contraception affects women in space.

More Research Is Needed on Women in Space

We should also consider how differently female and male bodies respond and adapt physiologically to radiation, microgravity, and other consequences of a rather harsh space environment. Research knows a lot about how space affects males, but not females. In the future, this is one area that space programs should focus on.

In our current decade, organizations like NASA and even private sector companies should invest in this progress we’ve made on diversity and inclusion, by ensuring we understand our female astronauts and why men still outnumber them nine to one in ISS crews. We should focus on how women experience the challenges of spaceflight and institutional culture. Further, space designers need to abandon a one-size-fits-all approach and instead focus on how to make a more customizable environment so females aren’t seen as deviating from a male standard. Differences in sex or gender shouldn’t be treated as obstacles.

In the space sector, we should all listen to the thoughts and experiences of women and continuously examine and actively work towards being inclusive in all areas of space exploration, from engineering to leadership. Making space for more women is not only more democratic but crucial for the future success of space exploration.